John Singer Sargent, on a visit to the Royal Academy in London, was approached by a student artist who rushed to express his enthusiasm for Sargent’s work. “Mr. Sargent," he said, “ I so much want to have a career like yours, but I struggle to find the right subjects.” “Turn around.” replied the artist.

John Ribble and Sue Medaris, two of the stars of the galaxy of talent represented by Abel Contemporary Art located in Stoughton, are debuting an exhibition this week entitled “Domestic and Divine”. What these two artists have in common is the way they draw their inspiration from the very essence of their daily existence: Sue from her life as an active farmer at the edge of western Dane County and John from his sojourns and knowledge of the intimate and unwatched spaces of this driftless region. Both of them becoming what Adam Gopnick would refer to as “radical realists," not because of their fidelity to representational rendering but because of their attention to the fundamental nature of the places they inhabit.

Upon entering the show it is hard not to be overwhelmed by Medaris’ nine and a half foot tall hand colored woodcut entitled ‘Cock o’ the Walk. The immense presence of this aggressive rooster virtually straining the boundaries of the picture plane as he strides towards the viewer might even be disconcerting for the timid soul. It evokes the astonishment that must have impressed the nineteenth century circus aspirant upon encountering the colossal posters of unfamiliar beasts. The scale alone befits the personality that Medaris recognizes in him. The masterful carving creates a bold graphic presence as he turns from the shadow and reveals the polychrome pride that compliments his attitude.

And yet this is not her strongest print. On its right is a fifty-three inch square woodcut, again enhanced by hand coloring, of a possum defending its kill as it emerges from the chiaroscuro depths. Mouth wide, teeth bared, slaver dripping from its mouth, the creature displays one of its characteristic survival postures. Seen from slightly below, enlarged to the size of a puma, Medaris offers an insight to the daily struggle of creatures that most of us have only encountered as road kill on rural highways. Again she employs a shallow depth of field to enhance the drama of this encounter and imbue her subject with its own distinctive persona.

Accompanying these woodcuts are a number of others including a close encounter with firmly grounded hog, a playful Great Dane puppy and another immense chicken contemplating a sky full of flying pies; perhaps a portent of things to come.

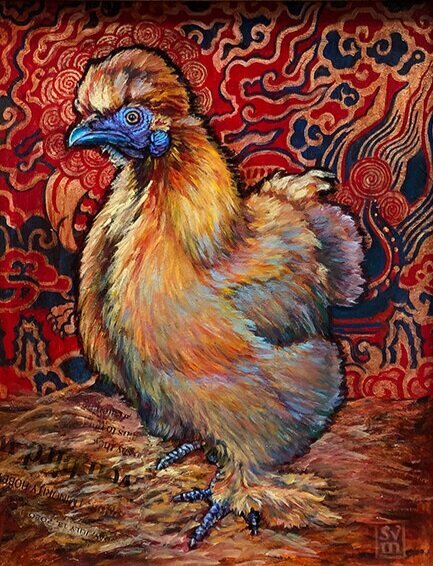

In addition Medaris gifts us with a collection of exquisite small oil paintings, painterly in aspect, rich in imaginative coloring, and deeply committed to eliciting the personality of her chickens from hatchlings to maturity. Included in this group are two paintings of Chinese Silkies, birds thought to have emerged during the Ming Dynasty and still intact as a distinct breed to this day. Mentioned in his 13th century diaries, Marco Polo mistakenly thought these unique chickens were covered in fur due to the distinct nature of their plumage. Medaris presents them with a backdrop of period tapestries and prefixes the titles with the phrase “My Pandemic Summer” making a wry and subtle reference to the Asian origin of both the chickens and the virus impacting all of our lives. The graphic strength of her over-sized woodcuts informs the strong contrast in these jewel-like paintings.

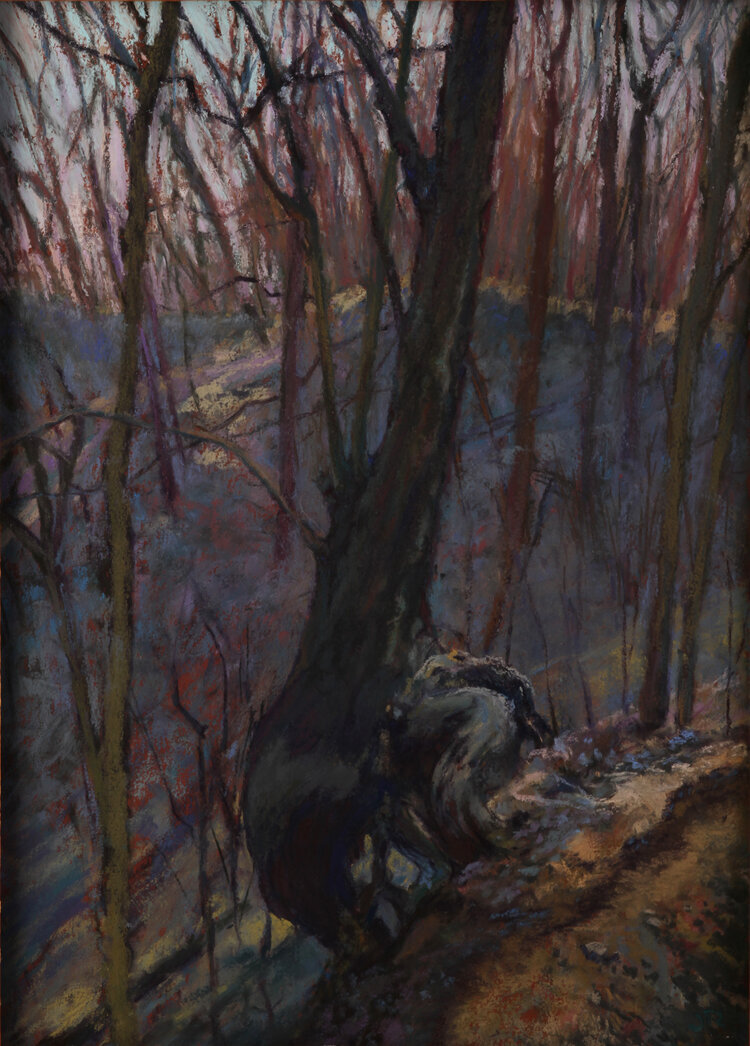

John Ribble, in contrast to Medaris’ magnification of her world, brings his stunning landscapes, all rendered in magisterial pastel work, to us in a pictorial scale of two to three and a half feet. Rich in spatial complexity, dense with detail and closely observed color notes, looking at Ribble’s work is like being admitted to the entrance of a secret garden, peering through a thicket of branches, undergrowth, leafed and barren foliage into a realm of almost magical color.

In French the word “repousser” meaning “to push back” has become a short hand term to describe the phenomenon of using a dark, often silhouetted shape, sometimes of great complexity, to force the viewer’s attention from the foreground plane into the deeper illusionistic space of the painting. Ribble seems intent to demonstrate the infinite capacity of this phenomenon to intrigue and entrance us into entering his visual playground. We are captivated by both the invention of nature and of the artist in finding new ways of entrapping us into closer and closer examination of his visual experience.

And it is experience that is the nexus of his creation. Ribble is calling attention to the very incidents of landscape that most of us would ignore. These are not the sylvan vistas of Constable, neatly husbanded to demonstrate the aesthetic interference of human hands upon the landscape. These are glances of unexpected wilderness that invite us to understand what we are on the verge of losing. Ribble is demanding that we ‘pay attention’ to serendipitous aesthetic that we ignore. “Quarry Park Moonscape” a dense entanglement of vertical rhythms, grounded at the fore by the exposed knotted root of a contrapuntal tree deepens into a universe of chromatic complexity and subtlety in a waning light. Three paintings in his “Rampike” series use the foil of up-rooted and dead or dying trees not only as a design conceit but to frame the distinction between the passage of time and death and the emergence of new life and intense luminosity in the deeper interior of the works.

John, like Sue, departs from his theme with a number of distinctly different images: two of Stoughton street scenes and one of the sentinel presence of a grain elevator in Black Earth. The commonality with his landscapes, all accomplished “en plein air”, or on location in the weather, is his intention to draw the viewer into an interaction with a visual event that would in most cases go unremarked upon. He recognizes and celebrates the abstract properties of the built environment, often constructed without regard for any of the surrounding elements. Now telephone and power poles substitute for trees, wires become the calligraphy of branches, doorways reflect the intense hues previously seen in glimpses of open water, and vistas expand both invitingly and perhaps with a suggestion of caution.

To have two such remarkable artists in our community is a form of grace: an unearned and perhaps undeserved gift, but like grace we must avail ourselves of its presence when offered. The privilege of having these artists so generously share their experience for our visual and contemplative pleasure should not to be taken lightly. This exhibition will be, not a moveable feast, but a passing banquet.

-Chris Gargan

Chris Gargan is a landscape painter living on a farm in Western Dane County, Wisconsin. Chris taught at Madison Area Technical College in the Graphic Design and Illustration program for over 37 years, retiring in the Summer of 2015.

Chris does almost all of his painting within a ten mile radius of his farm. He is deeply concerned about the disappearance of unspoiled rural areas and the pressure of real estate developers bulldozing farms and building large footprint luxury housing neighborhoods. Many of his earlier paintings depict views and vistas which no longer exist.

As an artist, Chris is deeply committed to the idea of art remaining strongly committed to principles of aesthetic integrity, authenticity of intention, and integrity of discipline. He lives in the hope that painting remains a vital and critical cornerstone of contemporary visual expression.